Attempts to increase taxation on revenues generated by large technology companies, most of which are based in the US, are jeopardising the consensus underpinning the international corporation tax system, says a top tax expert.

“The Internet and advances in telecommunications have smoothed the way for businesses to participate meaningfully in the economic lives of countries where they have no physical presence—and to do so without paying significant income taxes in those countries,” says Georgetown University professor Itai Grinberg in an article in the January edition of Foreign Affairs. “European governments, especially the French government, have attempted to impose digital services taxes on giant technology firms.”

France enacted a digital services tax last July that targeted big technology firms. It imposed a 3 per cent levy on gross revenues from digital activities involving French users as well as on revenues from digital advertising and online services within France.

In January this year, Italy introduced a similar tax. UK Chancellor of the Exchequer Sajid Javid said in Davos on 22 January that Britain still planned to introduce a digital sales tax despite suggestions from US Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin that America might respond with a punitive tax on UK car exports.

Almost 40 other countries including the UK are considering similar measures. Most apply only to companies with annual turnover approaching or exceeding $1bn.

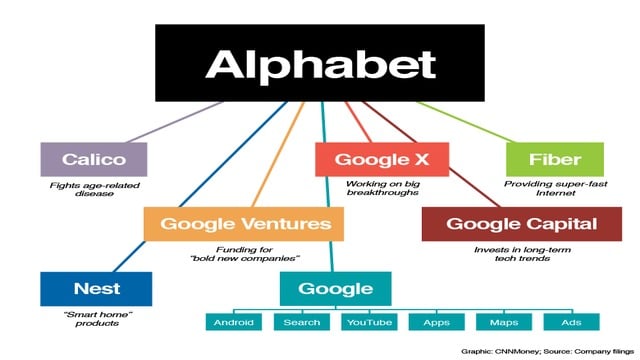

The US government opposes these measures, which mainly affect American corporations including Google. Washington could take countervailing actions that will involve taxing the revenues of French firms generated in the US.

The issue is complicated by the fact that countries imposing digital taxes continue to tax multinationals headquartered in their jurisdictions according to conventional rules.

This is increasing the risk of double, triple and even quadruple taxation. Companies facing this prospect are likely to withdraw from international trade with negative global implications, says Grinberg.

The OECD is sponsoring talks involving 135 countries about the issue and hopes to finalise an agreement reaffirming traditional rules by the end of the year.

The chances of this happening are slim.

But is there another way of dealing with the challenge to the international tax system presented by cross-border digital services sales?

Economics2030 argues the solution resides at the national level. Companies selling such services should be obliged to incorporate a local subsidiary to record all sales in a particular jurisdiction.

That subsidiary should in turn be required to have a paid-in capital that is fixed in proportion to the value of those sales. Part or all of that capital should take the form of physical assets in that jurisdiction.

Established tax rules could then be applied. It’s possible that governments, recognising the positive impact of fixed asset investments by such subsidiaries, might actually be willing to reduce taxation on corporate profits.

There are no quick fixes or easy ones.

But it’s increasingly obvious that government and business practices need thorough review to take into account the implications of the irreversible shift towards service good creation and the rise of intangible capital in advanced economies.