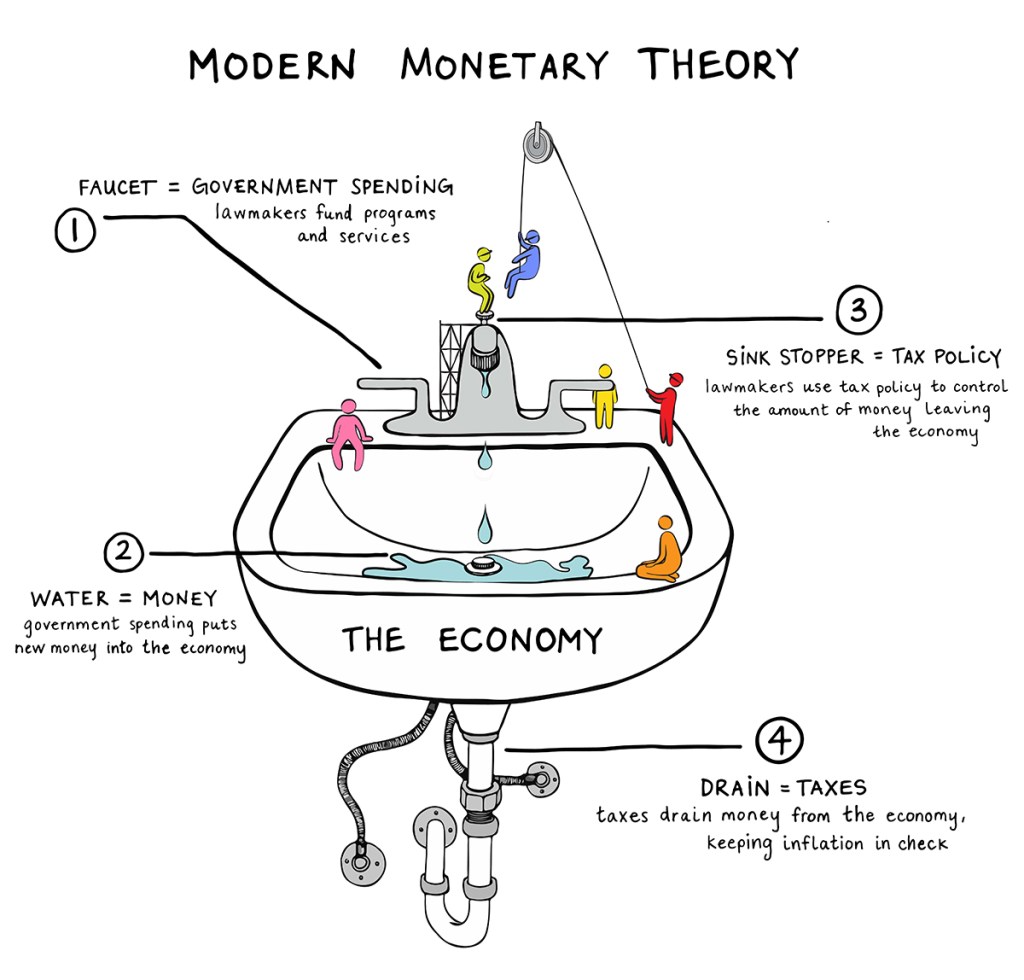

Credit: www.marketplace.org/2019/01/24/modern-monetary-theory-explained/

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is an idea that’s gathered growing support since the term was first coined in Full Employment Abandoned, a book published by Bill Mitchell and Joan Muysken, both academic economists, in 2008.

This is recent by the standards of economics, a discipline that has produced practically no conceptual innovations for more than a century.

But MMT is neither a new idea nor (as will be explained) a helpful one.

It originates in The State Theory of Money, a book published in 1905 by German economist Georg Knapp. He argued that money issued by a government was not a commodity but “a creature of law” that the state creates and commands. This is the central point of MMT too.

As legal tender, money must be used by individuals and corporate entities within the territory that the issuing state governs. And because it is the product of legislation not production, money requires no tangible inputs and can be “manufactured” with no physical limitations (unlike silver and gold commodity coins). In other words, governments issuing fiat money can never run out of it because they can always create more.

Contemporary MMT proponents provide an alternative way of looking at the way economies using fiat money operate. It starts with the government issuing money to pay for what it needs. That money returns to the government in due course in tax or in the form of loans.

“In essence, government can and does create money,” MMT champion Richard Murphy wrote in his blog in December 2020.“Government debt is just a means for saving private wealth. If you want government created money (and you do) the government has to run a deficit. There is nothing to worry about in this policy so as long as the economy is not overheated as a result.”

Originally named Chartalism, Knapp’s thinking influenced John Maynard Keynes, Hyman Minsky and Wynne Godley. But every government is now an MMT practitioner. No one believes that governments must pay off all outstanding public debt and it is not even an issue if it is deemed reasonable.

New UK premier Rishi Sunak, nevertheless, will target debt reduction as an early priority. It’s reported he believes the UK’s 100 per cent debt/GDP ratio is unsustainable particularly after the rise in the UK bank rate to 2.5 per cent (though this is still low by the standards of the past 50 years). Significant cuts in public spending are coming.

Sunak’s concerns infect the main opposition Labour Party which has declared its commitment to “sound money”. William Gladstone, British premier in the 19th century, would have approved.

So why are those who shape UK government policy rejecting MMT?

The first explanation is technical.

Increasing public spending without an appropriate monetary policy could lead to accelerating inflation, a pattern that discredited Keynesian macroeconomics in the 1970s. It might also produce a deterioration in the current account and depress the exchange rate which in turn accelerates inflation.

These are arguments that generations of economics students have been obliged to master. Those promoting MMT recognise this can happen too.

A second critique appeals to common sense. How can governments produce greater economic output simply by creating intangible fiat money?

This is the “Magic Money Tree” charge made against those calling for increases in public spending not financed by tax. It was one of the reasons that Sunak’s predecessor Liz Truss lasted less than 50 days in Downing Street.

Keynesians and economists working within that tradition say that an increase in public spending during a recession will lift investor and consumer confidence and that will boost aggregate expenditures. They also tend to argue that higher government spending is a way of making societies more equal.

MMT’s main appeal, however, is that it equips governments with tools to raise spending without politically-contentious simultaneous and equivalent tax increases.

Some say the theory sounds too good to be true, but it’s worse than that.

It’s the opposite of what modern economies experiencing low growth and struggling to finance infrastructure actually need. That is tangible assets which can be used to manufacture physical goods and support the creation of intangibles.

MMT has helped economies seeking to boost the output of tangible goods. But it’s ineffective when service production is dominant as it is in the UK where the proportion of output and employment due to tangible good manufacture is now less than 20 per cent.

The change, which is the most significant since the industrial revolution, has involved companies shifting towards creating services. Service industries require little capital. They are also inherently unprofitable.

Freed from the need for expensive machines and stocks of inputs and outputs, workers with skills that are in demand don’t need finance or the hierarchical managerial structures all corporations inevitably entail. They can work for themselves.

And yet giant corporations continue to dominate many economies. That is because profit for a growing number is increasingly due to intangible capital: intellectual property and financial instruments. Tangible items now account for only 10 per cent of the assets in the balance sheets of Britain’s largest corporations.

Intangible capital — like money according to MMT — is “a creature of law” with no inherent value. And, because it has no physical characteristics, intangible capital can no play role in value creation either.

Only machines and physical inputs can be used to make tangible goods. And you can’t create services that people need without supporting physical infrastructure like buildings and roads.

Intangible capital is developed using legislation and accounting codes. And it is providing investors with the principal means to make competitive returns in economies dominated by services.

MMT is the public sector equivalent. It’s government intangible capital. And like its private sector counterpart, MMT money can only survive by feeding off those who actually create value in manufacturing and in services.

This insight not only locates MMT’s core deficiency. It also leads to the identification of lasting solutions for pressing economic problems and not just in the UK.

The legal machinery that’s being used to generate massive and undeserved profits for corporations should be dismantled. And economics should reject public policy solutions that compound this dysfunction including MMT.

Instead, individuals and corporations should be encouraged to invest in physical assets and in government bonds that are issued to raise finance for the construction of the physical infrastructure and the creation of the universally affordable services that free and equal societies need to prosper. If half the intangible assets of UK corporations were converted into tangible assets, British output and employment would both be boosted without a penny of additional government spending.

This approach is subjectively appealing, logically sound and actionable.

And it will consign MMT to a footnote in the history of economic thought where it belongs.