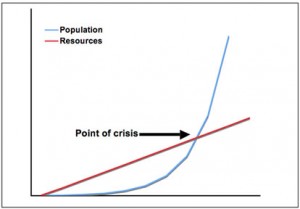

Graph sowing the principle of Malthus’ theory of population.

(Graph by Jan Oosthoek, Environmental History Resources)

In June 1798, an English vicar penned two sentences that in many ways defined the problem economists have tried to solve ever since.

“Population, when unchecked, increases in a geometrical ratio. Subsistence increases only in an arithmetical ratio.”

Thomas Malthus (see image below) placed this seminal thought in the first chapter of “An essay on the principle of population, as it affects the future improvement of society with remarks on the speculations of Mr Godwin, M Condorcet and other writers”.

The essay comprises more than 55,000 words. But it’s those 15 that echo through the ages.

Malthus’ purpose was to challenge assertions, inspired by the American and French revolutions, that it was possible for humanity and human society to be perfected by conscious management.

But Malthus was not an unambiguous supporter of laissez-faire economics. In other works, he argued that an economy could experience a long-term surplus of production and championed tariffs on grain imports as a way of promoting British food self-sufficiency.

Malthus’ scepticism about the benevolence of the unfettered free market was praised by John Maynard Keynes.

Malthus’ influence extended well beyond economics. Charles Darwin’s conclusion that life on earth was the result of the “survival of the fittest” can be attributed to his reading of Malthus in 1838, a couple of years after the completion of the HMS Beagle expedition to South America in which he served.

The first substantial sentence of The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection could have been written by Malthus:

“As many more individuals of each species are born than can possibly survive; and as, consequently, there is a frequently recurring struggle for existence, it follows that any being, if it vary, however slightly, in any way profitable to itself, under the complex and sometimes varying conditions of life, will have a better chance of surviving and thus be naturally selected.”

Darwinism inspired the eugenic movement that ultimately degenerated in its most extreme form into genocidal Naziism. It remains influential in natural and social science.

For economists, Malthus was both an inspiration and a challenge.

In 1932, LSE economist Lionel Robbins defined economics as being “the science which studies human behaviour as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses”.

For Robbins, the central issue was that there were too many people compared to the things they wanted. It was an adapted form of Malthus’ pithy, original observation.

Economists before and after Robbins have laboured to prove Malthus’ pessimism was misplaced and that humanity’s destiny is mutable. And they’ve also tried to show that society’s natural workings largely unaided could come to our rescue.

The contradiction at the heart of Malthus’ economics is that he asserted it was impossible radically to improve the human condition and yet government action could help stabilise economies. That paradox was finally resolved by Alfred Marshall in his seminal 1890 book The Principles of Economics.

He showed it was conceivable for self-serving individuals – the equivalent of the common people that Malthus depicted as driven by the need for food and sexual “passion” – to deliver a stable and efficient economic equilibrium so long as the market was allowed to function properly.

This insight was built on by Marshall’s disciples who theorised that targeted government action could correct instances where the free market ideal was obstructed and redeem the world from the fate Malthus prophesised.

History suggests the response to Malthus has been an overwhelming success. In 1800, the world population was 1bn. Today, it’s approaching 8bn and forecast to rise above 9bn in less than 50 years. Despite that, the overwhelming majority are sufficiently nourished. Average life expectancy for someone born in 2020 is around 73 years (in England in 1800, it was 40).

In advanced economies, the biggest cause of death and disability is not malnourishment. Diseases associated with too much food are now among the top killers.

If there’s one fact that economists can credibly point to as justifying their discipline, it’s this: government action inspired by their theories and advice has made the world a far, far better place.

And (it can be argued) that is because of Malthus’ warnings, not despite them.

But can that be said about the future?

Economic policies that invalidated Malthus’ dismal forecast are encountering a new truth.

The Malthusian pattern has not only been contained. It is being reversed.

The looming challenge is not too many people, but too few.

While life expectancy increased, the global birth rate in the past 60 years has fallen. In 1960, the average woman in Britain had 4.2 children. Today, the figure is 1.6 and dropping. The trend is even sharper elsewhere. In South Korea, the average woman has 0.9 children.

The only regions where births remain well above what’s required for the population to replace itself are the Middle East and parts of Africa. New projections suggest the world’s population could peak well before 2100. Some forecast that it will collapse thereafter.

The implications are profound.

As people live longer and have fewer children, the proportion of older people will grow. In 2050, a quarter of the UK population is forecast to be aged 65 or more compared with 20 per cent now. Most of them will be retired and dependent upon pensions.

Older people experience more health problems, notably neurological degeneration which is expected to affect three times as many people in the UK in 2050 than now. “Dementia is gradually becoming an overwhelming societal burden” an IMF report said in November.

The new long-term global outlook is that the population will fall and average age increase. This will lead to lower growth, higher income tax for a proportionately diminishing work force and a growing generational divide between those supported by the state and those paying for the state.

Can economics respond in the way it did to the original Malthusian prognosis?

Logic suggests that the conventional line of economic thinking should be inverted to reflect the Malthusian reversal.

The collective should displace the individual and managed institutions displace the free market in theoretical models. And interpersonal relationships – particularly between generations — not market price should be the key vector determining the allocation of resources and human effort.

For the moment, however, economics remains gripped by ideas developed to address a problem that soon won’t exist. But in due course it will have to come to terms with an emerging new world that Malthus couldn’t have imagined.