In 1890, Cambridge Professor Alfred Marshall published Principles of Economics, considered the first complete economics text book. Arguably, it’s the source of everything the discipline comprises.

Marshall’s key idea was distilled into a graph where demand and supply curves intersected at what is now known as the market-clearing price. This was a bliss point which was both technically and socially-efficient.

In theory at least, there was a price for all markets that would produce unimprovable outcomes from objective and subjective perspectives .

This idea has been challenged for 140 years but remains at the heart of economic theory taught at schools and universities. The debate is reflected in the sheer size of even the most basic text book.

But there was one issue that the theory, however much it’s qualified, simply couldn’t tackle.

How can it be applied to economies like the UK’s where 90 per cent of output and employment is accounted for by services, things which are created, sold and bought that have no physical characteristics?

The texts either ignore the issue or treat intangibles as if they were tangibles, something which makes no logical or semantic sense.

But so what?

As long as the economy in the long-term keeps on growing, which it has done since 1890, why should anyone worry about whether output can be physically sensed or just imagined.

But it seems the reckoning has finally come in the form of Covid, a lethal virus that no human consciously made or would want to have but is nevertheless turning the global economy upside down.

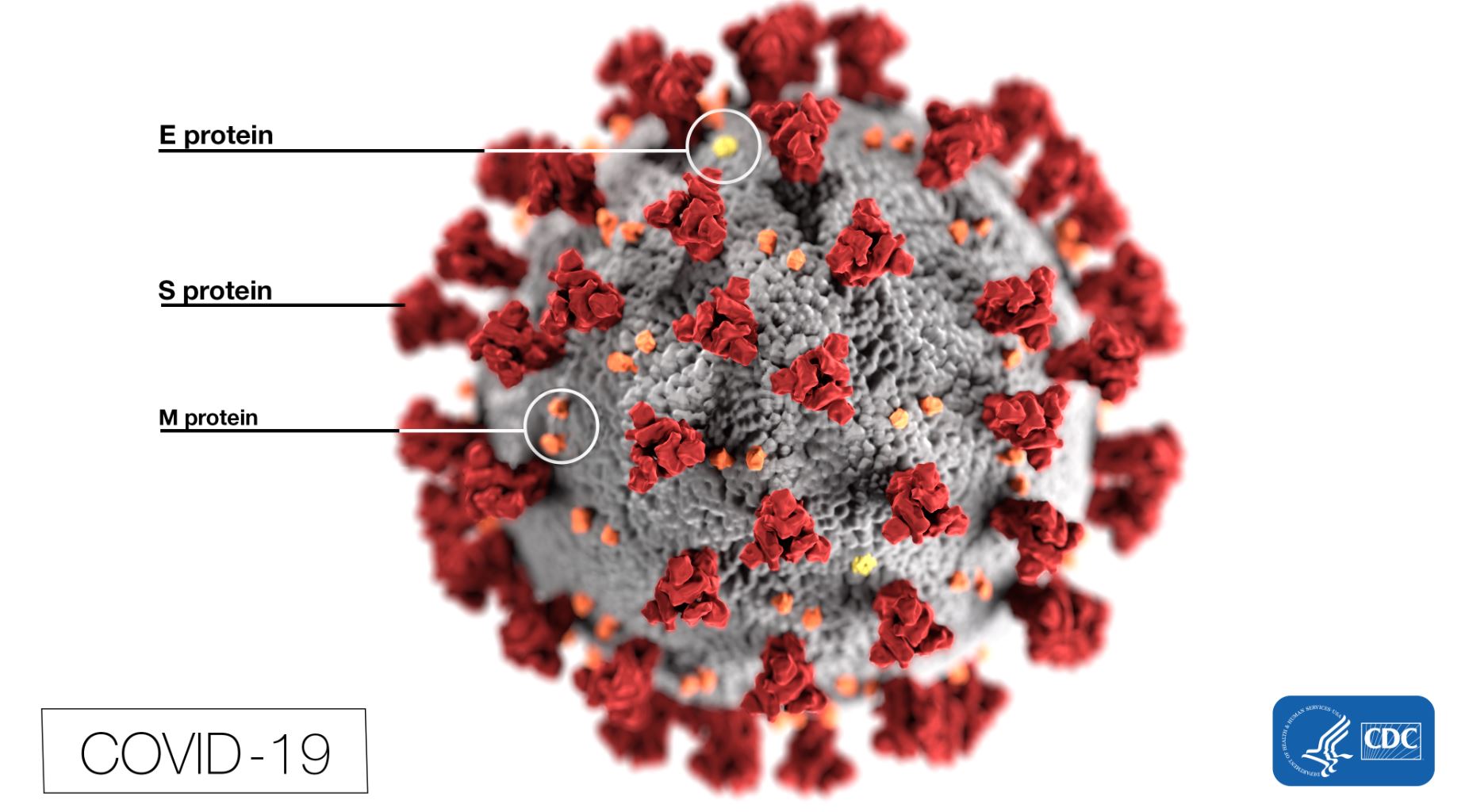

Covid has precipitated a global stock market crash…quite an achievement for something less than six months old and the eye can’t see

It was first identified in China in January. In less than two months, Covid has precipitated a global stock market slump, a 30 per cent oil price crash and what now appears to be the start of a global recession.

That’s quite an achievement for something that’s less than six months old and too small for the human eye to discern. And Covid will unavoidably affect our ideas as much as it already threatens our bodies.

That’s because it’s exposed the artificial distinction that originated with Marshall between the market on the one hand and people on the other.

Human action, of course, was represented in the professor’s famous graph. The supply curve distilled all physical and mental efforts involved in making what’s offered to the market. And the demand curve captured every human need and emotion it attempted to satisfy.

And yet, it looked like a machine that worked with no organising human agency. The market depicted by Marshall was both spontaneous and mechanical and, ultimately, everyone’s best pal as well.

This division between the market and people is one of the main reasons why many who haven’t studied economics hate the subject.

It’s not only because it encourages the idea that there’s nothing much you can do about economic trends. It’s also because the discipline does it in such an emotionless and apparently inhumane way.

It is for that reason that so many who’ve never read a book about economics admire John Maynard Keynes, a gay aesthete who coined the phrase “In the long run, we are all dead.”

That’s probably the most anti-economics statement any economist has ever written.

Nevertheless, there are more economists than ever. Top universities teaching the subject are oversubscribed and economics graduates are consistently recorded as having among the highest lifetime earnings.

They are unloved but, it appears, we can’t do without them.

So you would have thought that Covid’s impact on the global economy would have elicited from among their ranks penetrating analysis or even a bit of Keynesian wit to cheer us up.

In the short-run, we may all be dead, perhaps?

But no. Economists have almost nothing to say, or at least nothing positive.

It was perhaps best summarised by the headline on an article in Businessweek in its 16 March edition by the magazine’s economics editor Peter Coyt which read: “You can’t fight the virus without hurting the economy”.

You can imagine economists everywhere regretfully muttering their agreement.

For non-economists, this line of thinking not only sounds inhumane. It seems illogical.

For them, a person who gets sick is someone who also makes, teaches, heals and creates. Uncontaminated by more than a century of advanced scholarship at the world’s finest academies of higher learning, the non-economist doesn’t comprehend the distinction that economists live to explain between the market on the one hand and humanity on the other.

Surely, they argue, something bad for human beings, which Covid definitely is, must be bad for the economy. Making sure people don’t contract it, are effectively treated when they do and are free from fear that family, friends, customers and colleagues could catch it must be good economic policy, and not just in the long-term.

The official response, in contrast, has been to aid the market first. After all, every economist believes that’s what’s good for the economy must be good for people and, conversely, people will suffer if the economy does.

Within the framework of market-oriented thought, this makes sense, but only if you accept the idea that the production of goods is no different to the creation of intangible services.

But that’s totally wrong.

Value in services can only be created by constructive human interaction. And that’s impossible if the people involved in that interaction are sick or fear their counterparties have or could get the virus.

Coyt’s headline should have read: “You must fight the virus if you want to help the economy”.

The priority must always be people. Look after them and the economy will look after itself

…there is no trade-off between having a healthy population and economic growth.

What does that mean for policymakers grappling with the economic consequences of Covid?

The first priority is for them to recognise there is no trade-off between having a healthy population and economic growth.

Resources should be mobilised to insulate as many as possible from the virus and its future permutations and provide the means for them to look after their health and that of their family and friends at the lowest possible cost.

This largely conflicts with the thinking underpinning the Covid strategy unveiled last week by the UK. Promoting herd immunity by allowing the pandemic to develop naturally but in a controlled way makes sense on someone’s laptop. But in practice, it is impossible.

How can you expect people to behave optimally when they know a killer virus is being allowed to envelop everyone they know, need and love?

Only those lacking imagination wouldn’t be gripped by anxiety and fear.

That was exposed almost immediately after British Prime Minister Boris Johnson defined his policy on 12 March. He said there would be no ban on mass gatherings. But his government announced the following day that legislation to do just that would be put to parliament.

Johnson’s opposition to closing schools will probably be overturned soon as well.

Keeping schools open makes sense, but not if you’re a teacher, particularly an older one with aging relations…

The herd immunity injunction Johnson implicitly supports is that children — less likely to get seriously ill because of Covid — should be exposed to the virus and school is probably the best place for that to happen.

Sounds sensible, but not if you’re a teacher, particularly an older one with aging relations, it doesn’t.

Unsurprisingly, people at the heart of value-creation in schools, universities, hospitals and care homes are pointing out that it can’t work and won’t.

Epidemiologists probably should never have been allowed to dominate policymaking about a challenge with such enormous implications. But that’s only happened because social scientists in general and economists in particular have almost nothing constructive to say about Covid.

There’s an intellectual gap that needs filling with economics’ valid insights, particularly about how value is actually created in service economies.

Let’s call it Covidnomics.

There could be a Nobel Prize in it.